|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

AACR news

June 15,2016

Presurgery Chemotherapy May Make Advanced Ovarian Cancers Responsive to Immunotherapy

“We are studying a type of ovarian cancer called high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSC), which is quite difficult to treat for two main reasons: first, it is often detected after it has spread quite extensively in the body; and second, although the disease can respond well to the first chemotherapy treatments, it often relapses and becomes more difficult to treat. Therefore we need to find other treatment options after the initial treatment is given,” said Frances R. Balkwill, PhD, professor of cancer biology at Barts Cancer Institute in Queen Mary University of London, United Kingdom.

Prior preclinical research in mice suggests that when chemotherapy destroys cancer cells, it also stimulates immune cells in the cancer that can kill cancer cells, explained Balkwill. “We wanted to study whether this was also true in cancer patients, and whether it occurred with the chemotherapy used to treat women with ovarian cancer,” she added.

“Our study showed that chemotherapy altered the immune cells called T cells that are found in metastatic ovarian cancer samples in a way that suggested they were better able to fight the cancer after the treatment. Our research provides evidence that immunotherapy may be more effective if given straight after chemotherapy,” Balkwill said.

Balkwill and colleagues collected pre- and post-chemotherapy biopsies and blood samples from 54 patients with advanced-stage HGSC who underwent platinum-based neoadjuvant (given prior to surgery) chemotherapy, and from six patients who underwent surgery without prior chemotherapy.

The researchers analyzed the samples using immunohistochemistry and RNA sequencing to study the changes in the tumor immune microenvironment of patients who received and did not receive chemotherapy, and changes before and after chemotherapy. Patients were categorized into those who had a good response and those who had a poor response to chemotherapy, based on a recently approved chemotherapy response score that correlate with progression-free and overall survival.

They found that in patients who received chemotherapy, there was evidence of activation of certain types of T cells that can fight cancer cells, while the number of a type of T cell that suppresses the immune system decreased. The results were more pronounced in those who had a good response to chemotherapy, compared with those who had a poor response to chemotherapy.

“Although we found that chemotherapy activated the T cells, the levels of the protein PD-L1 [to which the immune checkpoint molecule PD-1 binds to disable T cells and prevent them from recognizing and destroying the cancer cells] remained the same or increased. However, immune checkpoint blockade therapies [such as pembrolizumab and nivolumab] can stop this from happening, so we suggest that immune checkpoint blockade might be a suitable form of immunotherapy to give to ovarian cancer patients after chemotherapy,” Balkwill said.

The team also found that chemotherapy reduced the blood levels of certain cytokines—inflammatory molecules that promote cancer growth—often back to normal levels in patients who had a good response to chemotherapy. “This could help immunotherapies work better,” Balkwill noted.

“The chemotherapies, carboplatin and paclitaxel, given in our study are also used to treat many different cancer types. It will, therefore, be very interesting and potentially promising if similar effects are seen in other cancer types, such as lung cancer,” she added.

According to Balkwill, a major limitation of the study was the small sample size, which also prevented them from analyzing pre- and post-chemotherapy samples from the same patient in some cases as there was not enough material.

The study co-authors include Steffen Böhm, MD; Anne Montfort, PhD; Oliver M.T. Pearce, PhD; and Michelle Lockley, MD, PhD.

The study was funded by Swiss Cancer League, the European Research Council, Cancer Research U.K., and Barts and the London Charity. Balkwill and the study co-authors mentioned above declare no conflicts of interest.

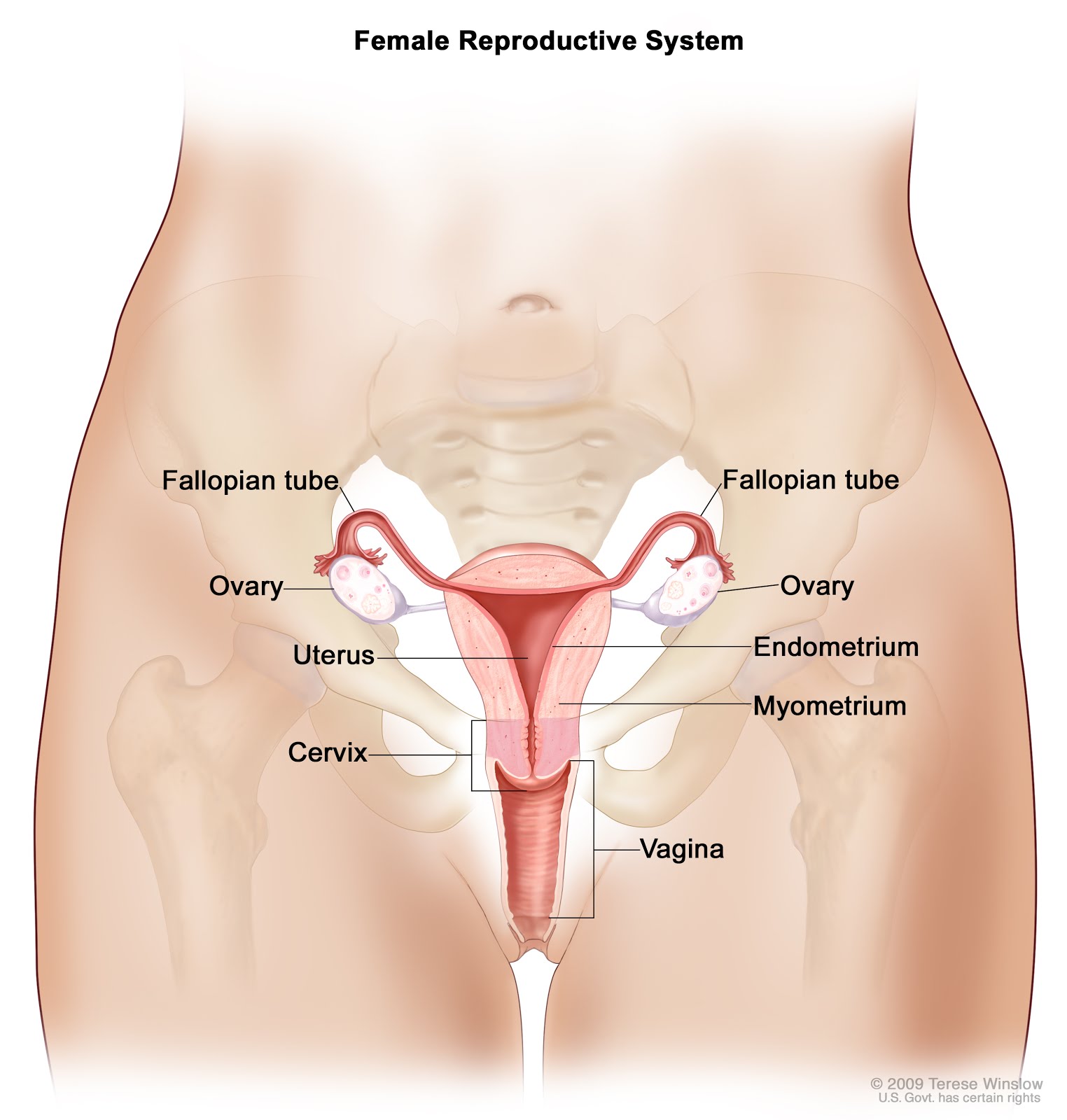

For more information on ovarian cancer, click here.

0 comments :

Post a Comment

Your comments?

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.